VISUAL SIGNS OF AMERICAN HERITAGE Part. I: Family Marks Rooted in Land, Range and Craft

Part One

In the American West, family heritage often originated through herd and craft — emblems of continuity preserved across generations.

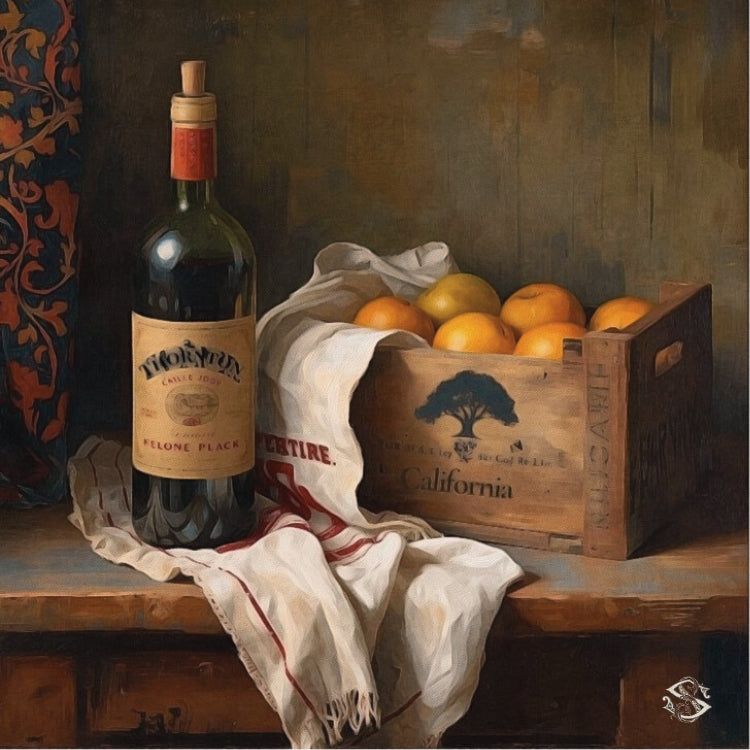

Families tied to the land have long carried their heritage forward not only through what they cultivate and raise, but also through the visual signs that mark their labor. What may begin as a functional identifier — a crest on a bottle, a stamp on leather, a brand on cattle — becomes an enduring emblem of family identity, passed from one generation to the next. These marks are heritage in plain sight, anchoring families to continuity even as agriculture and society evolve.

From the Land: Harvests Carried Forward

Across the United States, families tied their agricultural products to distinctive visual marks.

From the late 19th century through the mid-20th century, orchard growers in California and Washington shipped fruit in wooden crates adorned with colorful lithographed labels. These vibrant images often featured the family name, ranch insignias, or regional symbols, turning packaging into a canvas of both practicality and pride.

Milling families across the Midwest and West followed a similar practice. Beginning in the late 1800s and lasting well into the 1940s, flour and grain sacks were printed with bold typography and identifying marks that connected the grain to the family or mill that produced it. These everyday textiles, many later repurposed in homes, carried family signatures that traveled with the harvest to distant markets.

Among these varied signs, perhaps the most recognizable — and the most enduring — are found on wine labels. Vineyards, like farms and ranches, often used crests, names, and estate imagery that became inseparable from the families themselves. A leading example is Wente Vineyards in California’s Livermore Valley, founded in 1883 and still family-owned today. Now in its fifth generation, Wente remains America’s oldest continuously operated family-owned winery, with labels that have carried the family’s name and identity across nearly a century and a half. Each bottle serves not only as a vessel for wine but also as a public emblem of family stewardship and continuity.

From the Herdsman: Brands Carried Forward

For ranching families of the American West, the cattle brand was more than a practical identifier — it was the signature of the family itself. The practice came north from Mexico, where vaqueros had long branded livestock, and by the early 1800s brands were being formally registered across the U.S. frontier. Once recorded, a brand rarely changed, becoming a permanent emblem passed down through generations.

These marks extended far beyond the herd. Family emblems were etched into working gear — belt buckles, spurs, saddles, and tack — and also into everyday life, appearing on ranch gates, stone entries, and even correspondence. To families, the brand was both a legal claim and a moral covenant: a symbol of identity, reputation, and stewardship. Passing it to the next generation carried the weight of inheritance, binding land, herd, and name together.

A defining example is the Running W of King Ranch in Texas, founded in 1853. Nearly 175 years later, the brand still signifies more than cattle ownership. It represents a reputation trusted across industries, appearing not only on livestock and horses but also on products from apparel to leather goods to home furnishings. The endurance of the Running W illustrates how a family mark, first carried on cattle, became an emblem of authenticity and continuity — trusted wherever it appears.

From the Artisan: Craft Carrying Forward

In the American West, the vaquero tradition emphasized everyday gear as heirlooms. Cowboy culture, and vaqueros in particular, treasured each piece of silver and leatherwork they owned. Spurs, saddles, bridles, and boots were not only functional but symbols of pride and artistry. Carefully maintained and passed down, these items carried the stories of their owners, ensuring that craft and heritage lived on long after the first rider was gone.

Building on this tradition, saddle makers, silversmiths, and bootmakers left lasting signatures in their work. In Elko, Nevada, G.S. Garcia became sought after for the mark that signified the quality of his saddles and silver-adorned gear — recognition that reached the world stage when one of his saddles won a gold medal at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Since the late 1970s, the legacy of the Garcia Bit and Spur Co. has been carried forward by the Wright family through their stewardship of J.M. Capriola & Co. The iconic storefront has become emblematic of the authentic Western vaquero lifestyle, preserving a tradition of craftsmanship and culture for future generations. This continuum of American-made craftsmanship is also embodied by Anderson Bean and Olathe Boots. Stewarded by the Evans family under the Rios of Mercedes Family of Brands, both remain rooted in Texas and reflect enduring excellence that defines American bootmaking.

Visual Threads of Continuity

From the land to the herds to the artisan’s bench, these marks are more than identifiers: they are visible threads of continuity. As agriculture modernizes and traditions risk being overshadowed, enduring emblems of land, livestock, and workmanship remain anchors of authenticity — honoring origins with reverence while safeguarding integrity and ensuring family legacy remains relevant and distinguished for generations to come.

~~~~

This article is authored by Kristin M. Thornton, founder of K.M. Thornton & Co.. Her Arc of Stewardship™ framework guides families and heritage brands in preserving authenticity while carrying their legacy forward with distinction. For further insight, visit kmthornton.com.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.

Also in Essays of Legacy, Heritage and Continuum of Care

THE MOST GENEROUS GIFT: Passing Legacy Through Heirlooms

COFFEEHOUSE HERITAGE: The Luxury of Ritual Over Transaction